Vitalstatistix spoke with artists Mish Grigor and Rebecca Meston about feminism, new writing for performance, the value of residencies and their relationship to Vitalstatistix.

Rebecca Meston is a South Australian-based writer and theatre-maker. Her work has a particular focus on contemporary storytelling, tragi-comedy and the exploration of subversive female voices. In May Rebecca and her creative team will undertake an Incubator residency with Vitalstatistix, developing a new performance work called Drive. The team will present showings and talks on the 12th and 13th of May at Waterside.

Mish Grigor is an artist whose work investigates the relationships between popular entertainment and experimental art practices. She has an ongoing fascination with new writing for performance. In August Mish will co-lead this year’s Adhocracy residency project, Second Hand Emotions. Applications by South Australian artists to join this residency close on the 29th of May.

Vitalstatistix: Each of you is engaged in new feminist writing for contemporary performance, sometimes in a collaborative process with other artists. Can you talk about your process as a writer?

Rebecca Meston: My theatre practice began at PACT centre for emerging artists in Sydney –where I began exploring how I wanted to write, and the type of processes that fit with my ideas. At this time I worked with very rigorous practitioners like Chris Ryan (Sade/Marat), and Nikki Heywood (No place. Like home). In this black box space opposite a railway line in Erskineville, we created brand new work in a deeply collaborative way, pushing ideas and experimenting with form.

Since then I have created a number of original shows, just-about-always in a collaborative way, and with artists from a range of disciplines including writer/director Daniel Evans, sound designer Nathan Stoneham, choreographer and dancer Leah Shelton, comedian Nikki Britton, clown and theatre maker Hew Parham, performers Ray Chong Nee, Kate Skinner, Amy Ingram and Miranda Pike and Brisbane-based dramaturg Saffron Benner, who is a champion for the seeds of original ideas and where they might venture on stage. In 2015 I was awarded first prize in HotHouse Theatre’s Solo Monologue Competition for my piece Last of the Corsetieres about a very complex lingerie fitter named Gloria.

Mish Grigor: My process as a writer is messy, unformed and constant – I have hundreds of half-filled notebooks with indecipherable sentences. Recently in Britain I was at the theatre and someone pointed to an empty chair next to me, saying: “Is anybody sat there?” a sentence structure that I found delightful at the time. I noticed it in my notebook this morning, surrounded by three boxes and four ticks, with an arrow from the next page saying ‘USE THIS. GOOD.’

I’m not sure where it’s going, but I suppose it’s useful to know what you like.

I ALSO WRITE IN ALL CAPS IN FIRST DRAFTS, NOT SURE WHY. IT ALLOWS SPACE FOR A SECOND DRAFT THAT LOOKS DIFFERENT MAYBE?

When it comes to turning my musings and weak jokes into performance material, I think it’s a strange alchemy of formal experiments and weird hunches that force a sentence off the page and into action.

One of my favourite things is co-authoring a piece with someone. I think because I started making performance with POST when I was eighteen, I’ve learned to think best when with, or against, other brains. It seems bonkers to me that one person can form an idea, and birth it into the world perfectly formed. I don’t know anyone who works that way, even novelists, so I suppose it’s about finding the right place on the sliding scale of collaboration for each project.

V: What is the place of humour, comedy or satire, in your work or work you love?

RM: Satire, along with contemporary clowning, bouffon and comedy, is where the truth and the most devastating and heartfelt parts of humanity in art live. Stripped-back, ugly, shitting the bed, everything-Instagram-feeds-aren’t, honest truth. It’s the only place that can be truly funny, but also that holds any real meaning. All five seasons of Louis C.K’s Louis (but particularly the 5th) is a perfect example of this.

More recently his tragedy Horace and Pete with Alan Alda and Steve Buscemi, mines the territory of nostalgia, time, politics and grief – and somehow captured a feeling of hopelessness ringing so loudly in the lead-up to the US election when it was released.

On stage, the creation and performance of Dave, by Zoe Coombs Marr, is triumphant in provoking deep humour and thought in equal measure. I really, really like Dave. He’s likable.

And if you’ve ever seen it [Dave], you’ll know what an accomplishment of performance and character creation this is, given that in Dave she’s pulling apart the complexity of misogyny and ingrained sexism. Yet for the entire show s/he is charismatic, sincere, surprising, and truly laugh/cry funny.

MG: As a human I find laughter a useful strategy for survival in a world where days regularly seem insurmountable. As an artist, I think humour is a nice way of getting instant feedback from an audience – you really know that you’ve lost people if your ‘quip’ is met with stony silence… As an audience, I think I’m seduced by jokes into reconsidering the banal or taking the pressure off awful awful realities.

I have to say I am also suspicious of the potential tyranny of searching for laughter in an audience. I think we do this a bit too much in Australia sometimes.

But then again, life is hilarious. The construction of such everyday things – museums, dinner parties, queues, Le Snacks. How did we start doing things in certain ways? And how did we teach each other the rules? So much time is spent exercising rituals of nonsense, I can’t help but laugh.

V: What are some of the most interesting discussions and debates within feminism, for you right now? How has your feminism changed over time?

RM: A key cultural touchstone for Drive has always been Thelma and Louise, Ridley Scott’s 1991 revolutionary film, as it tracks a female road-trip across America. It’s so boring to keep banging on about this, but the film is revolutionary because the story was written by a woman (Callie Khouri); at the time of filming Geena Davis and Susan Sarandon were 35 and 45 respectively; they talk to each other a lot on screen; and their pursuit is about something other than a man, or men, or being validated by having someone put-a-ring-on-it. This film is now 26-years-old.

During the last International Women’s Day a lot of friends posted pictures of Beyoncé on Facebook and her lyric, “who run the world? Girls”. After the critical first turning point, when Thelma suggests that they turn themselves in, Louise says, “Who’s gonna believe us? We just don’t live in that kind of world” and then Thelma’s final line, “Something’s crossed over in me and I can’t go back…I mean, I just couldn’t live”. That this film is so one-of-a-kind still, and tells such a pertinent, relevant story, and that the same old power structures across all of the institutions remain the same, is hugely motivating for me, and the work I hope to make.

MG: I think it would be strange for someone’s feminism not to change, because it’s a lived experience, rather than a dogmatic belief system. My feminism right now is totally the feminism of a white, thirty three year old, Australian who makes angry art, who takes holidays and who has no dependants. Some of those defining features may change, some won’t.

I recently found myself sitting in between a seventeen year old still in her school uniform and a sixty five year old sociologist who had fought many public battles. They were locked in argument about their feminisms, about extremism, about revolution, about naivety, about change. They were both relishing driving each other mad with their different perspectives.

I think that the most interesting debates right now are the messy ones, the angry ones, the ones where intersecting ideas at cross purposes sit right in a loud conflict. I used to want to ‘solve things’, but these days even clarity sounds like the patriarchy talking.

V: Rebecca, can you tell us about your new work Drive? What fascinates you about the real-life story it is inspired by?

RM: Drive is exploring the 2007 story of astronaut Lisa Nowak – as its point of departure – to make a highly physical theatre show. In February of that year, seven months after she was launched into space on the Discovery shuttle, Nowak drove for 14 hours from Houston to Orlando to confront her lover’s much younger lover, while wearing a wig, trench coat and glasses, and was subsequently charged with attempted kidnapping and initially, attempted murder.

I live in regional South Australia, so started thinking about this story a lot when driving across long stretches of freeways and highways at night amid trucks and utes and a world and language of men – the world seeming so big and so terrifyingly small at the same time.

These thoughts were combined with an ongoing interest in biography and autobiography and the dance between truth and facts; in the mythology of NASA/space travel; and the mythology of women having it all. I was also intrigued by disguise and alter egos and the question: how can a woman so accomplished, so at the top of her game, fall so far from grace?

V: Mish, you have been presenting your solo work The Talk over the last year or so. Can you tell us about this show and the experience of taking it to different audiences?

MG: In The Talk, I ask audiences to re-enact with me a series of interviews I undertook with my family about sex and sexuality. Presenting my work most recently in the UK feels at once entirely instinctive and completely alien. There’s an artistic lineage (one of ‘live art’) that lands me back there quite comfortably, and yet the cultural and social conditions are complex mysteries.

The Talk is also a properly confessional overshare of a show. Performing something so intimate, full of inside jokes and wobbly family politics, so far away, has created a new tension in the work that I’m still getting my head around.

Some things fall flat (they don’t know what Pizza Shapes are!) and other things grow enormous in a new significance.

I’ve also been gobsmacked by the survival instincts in the UK performance scenes, soldiering on together against all odds.

V: Each year for Adhocracy, Vitals host a collaborative residency project where guest artists lead a process or creative development with participating South Australian artists. Rebecca, in 2014 you participated in this residency (in that year a project called Future Present, led by Rosie Dennis.) How did you find this experience and what is the value of this annual opportunity for local artists?

RM: The experience was extraordinary. At the time I had a 5-month-old baby (with me most of the time), and this project allowed me to return to my practice and engage with one of the most brilliant arts makers in Australia. This would not have been possible without Adhocracy.

It’s also where I worked with artists like Ashton Malcolm, Josie Were, Meg Wilson, Susie Skinner, Edwin Kemp Attrill and Alysha Herrmann for the first time – who have all become critical people to either work with or watch. Plus, I was developing work about one of the most urgent and critical issues to date – and in fact, the ideas we grappled with then, and ideas I started turning into story, have never left me and I hope to push them further in coming years.

V: Mish, also in 2014, for Vitals’ thirtieth birthday, you spent time with us developing your residency-made work Man O Man with local collaborators, after first presenting this performance event at Arts House, Melbourne. Can you tell us a bit about this experience and the work itself?

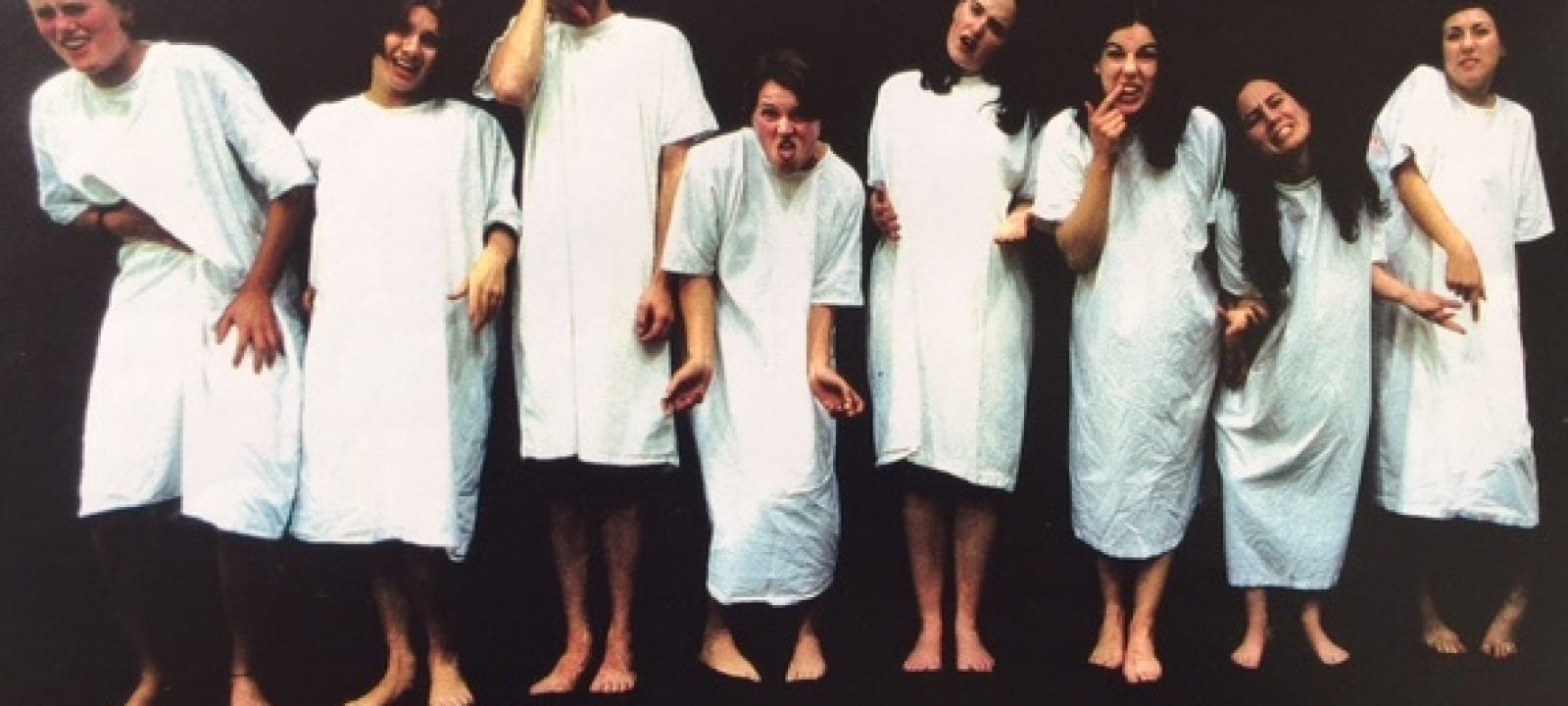

MG: In ‘Man o Man’ I invited Anne Thompson, Josephine Were, Celeste Aldhern, and Jane Howard to think about what might happen on the last night of the patriarchy. We were also joined by Meg Wilson, Gemma Beale, and Sophie Byrne.

The project, which also had a Melbourne iteration, was about providing a fantastical notion as a starting point for generative writing and the creation of performance possibilities.

It was also a context for a bunch of angry feminists to sit in anger together. I say without irony that it was one of the most special times of my art/life.

V: Mish, you are co-leading this year’s Adhocracy residency project Second Hand Emotions with SJ Norman and Sarah Rodigari. You will be joined by up to ten local artists, to explore the theme of ‘love and feminism’. What are you looking forward to with this residency?

MG: Last time I was at Vitals I started to learn about the feminist histories of the company and of the area. I think I’m looking forward to delving more into that. Also Sarah Rodigari and SJ Norman – what legends!

V: Rebecca, how are you approaching your Incubator residency for Drive and the opportunity to show the work-in-development in front of an audience at the end of the fortnight?

RM: Working with Roz Hervey and Larissa McGowan, dramaturg Saffron Benner and two very vital performers Ashton Malcolm and Jo Stone, Director Sarah Dunn and I are excited about prizing upon the material to find the scale and the stakes of this story.

It’s a true collaboration and we’re working from the ground up. As I’ve spent almost ten months researching this world, reading everything I can get my hands on, watching endless rockets blast off into space, it’s feeling like a very charged moment in time: turning all of this reading and writing into theatre. And to be honest, it’s a relief to finally have other people to share my obsession with.

V: Other than championing feminist performance and art (which goes without saying!) what do you value about Vitalstatistix in the current arts landscape? What role can small organisations play in supporting independent artists in these very lean times?

RM: Vitalstatistix is a centre for new Australian work that’s original, progressive and often developed from scratch on its beautiful wooden-floor boards. Like PACT was for me as an emerging artist, Vitals is a safe space (space to fail, and home away from home filled with like-minded souls); a space of deep exploration and risk; a space to challenge yourself and push your potential. In this current arts landscape – but also political, social, global landscapes, that are screaming out for original work that responds to the here and now,

Vitals invests in artists, understanding that new work takes time, nurturing, and a space for ideas to reach their proper fruition.

MG: What I observe in Vitals is an investment in practice, an investment in long term conversations with artists that might take many forms across a lifetime. Generosity goes both ways in this model – Vitals works hard to provide a space for artists, and the artists work hard to honour opportunities – as well as being ambassadors for the company elsewhere. This is very special in what feels like a tumultuous time to be an artist in this country.

With the funding bodies struggling to reassemble after the lacerations of recent political tyrants, namely the defunding of the Australia Council for the Arts by the current government, and the resulting instability. With organisations squirming to survive whilst doing more for less, I think it’s important to remember that as artists we are, in some ways, at the bottom of the food chain. We love our job so much, we feel enormously privileged when we are given space to voice our ideas or to be seen – and yet our survival can be entirely precarious.

We must be sure that we’re not becoming perfect neoliberal subjects, pleased to work always and wherever, without pay or protection or sometimes even community. Small organisations can be instrumental in valuing the place of artists who might otherwise be at sea in these circumstances.

I think things are changing in the Australian arts in ways we cannot quite see yet – these last few years have been a storm we’re still weathering. And the last eighteen months in politics, near and far, seem farcical and tragic. I think everyone is scrambling and determined and relentlessly stubborn in our fight to continue, to listen to each other, and to find resilience in solidarity. Also, coffee helps.

V: Current favourite feminist writing (fiction or non-fiction)?

RM: This is almost exclusively via the stage: Emma Beech, Patricia Cornelius, Betty Grumble, Briony Kimmings, Zoe Coombs Marr, Adrienne Truscott. Then there’s Carrie Brownstein’s memoir Hunger makes me a modern girl, and a world I just didn’t want to leave.

MG: I’m always hesitant to name a ‘favourite’, but this week I’m sitting in Karpathos, an island off Greece. I’m staying in an abandoned yoga retreat owned by a Norwegian but currently squatted by a Romanian gardener. I’m saying this partly to boast but also because it gives me plenty of time to have four or five things on the go – I’m reading Rachel Cusk which I’m loving, Siri Hufsted’s book of essays ‘Woman Looking at Men Looking at Women’, and the Documenta catalogue that’s looking at cultural imperialism as a curatorial context. I’m revisiting Bojana Kunst and Elena Ferrante for research. And next I’ve got Sarah Schulman’s ‘The Gentrification of the Mind’. In that mix there’s lots of good thinking.