Isolation Conversations is by Shopfront Artist-In-Residence Jane Howard. Jane speaks with Kate Power about how COVID-19 has affected their work, their process and their lives.

By the time Kate Power and I find time to talk in late May, the lockdown restrictions in South Australia are already starting to lift. Both at home, with few places to go and little to do, we have still struggled to find the time to meet. Time between our emails stretches out as life gets in the way. Finding a window where we can both speak is surprisingly hard.

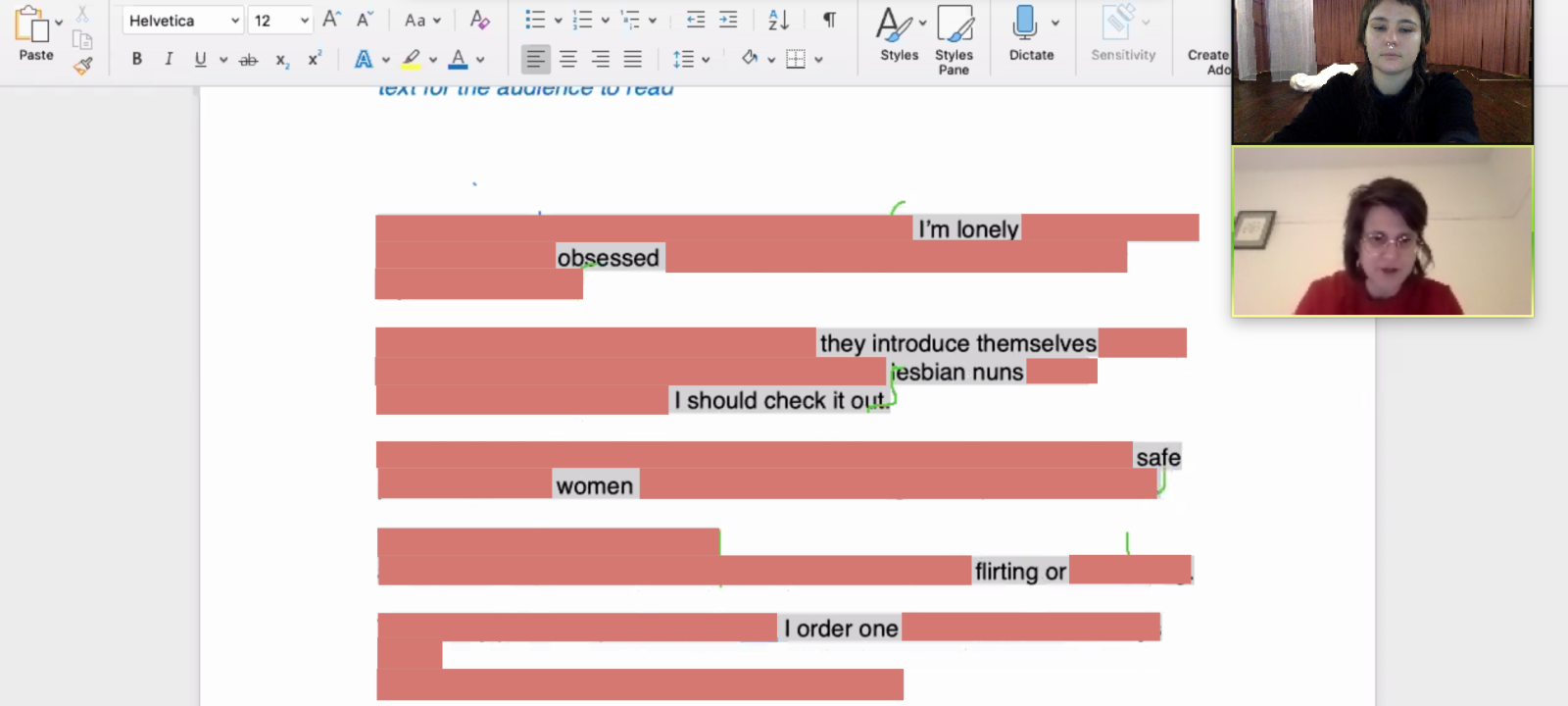

Finally, we find an evening to talk over Zoom – the video platform which so rapidly became an essential service in our lives.

“I’ve been so full up,” Power tells me about this strange sense of never having enough time. “Time-busy at the [book] shop [where she works], but also just emotionally quite full, I guess, like everybody is.”

Power was to be the first artist in residence at Vitalstatistix this year with her new work, Bedroom, under the mentorship of Sydney-based artist Sarah Rodigari. Scheduled for the 16th to 29th of March, in the week leading up to the residency it was two-and-a-half months after China alerted the World Health Organisation of an unusual pneumonia, one-and-a-half months after the first cases in Australia.

While numbers of the infected and dead were growing in China, Iran, the US, and Italy, Australia still felt relatively isolated and safe, with less than 300 cases. Melbourne’s Grand Prix was cancelled, but Adelaide’s festivals powered forward. “You could still fly,” says Power. “Things were less strict.”

“There was less awareness of what was going to happen.”

As the residency dates neared, Power and Rodigari started thinking of contingency plans: perhaps they could work together for the two weeks, and then quarantine themselves after. “I was kind of like, ‘oh, after Sarah leaves I’ll just quarantine for two weeks and it’ll be fine,’” Power says.

“And Emma [Webb, Director of Vitalstatistix] said ‘to be honest, I don’t know if you are going to quarantine for two weeks, given that you’re willing to do this.” She laughs.

Lockdown rules rapidly escalated. Bans on gatherings of more than 500 from March 16, then on more than 100 from March 18. “Non-essential” businesses closed from March 25; the same day South Australia enforced border controls. The staff of Vitalstatistix transitioned to working from home. And Power and Rodigari started their mentorship via Zoom.

Waterside Workers Hall, says Power, “was totally empty. There was this vast feeling of a huge space, of all this time, to make my work in there. It was exciting, but also quite daunting at the same time.”

Bedroom is an exploration of trauma, but the world Power started making the work in is drastically different from the world we now find ourselves in. “I was so ready to tap into that [trauma],” she says, “and to just embody it in my work and to fully try and open it up and now it feels like … What does that experience mean in this time? And it feels so distant now.”

“It feels a bit like you’re working through mud when you’re still trying to work on your other thoughts and projects.”

While lockdown forced Power’s residency to take on a very different shape over those two weeks, this shifting amorphous state has continued. With the hall sitting empty, no longer being used for performances or weddings or development, Power has continued to go back: this vast chasm all for herself.

Every Wednesday, for two hours, she and Rodigari keep working together. It has been a new process, one of “just chipping away at something slowly.” It is, she says, “not a luxury you really ever get.”

“I was meant to have a showing at the end of this, but of course that’s not happening. What can happen now that there’s time and space and in-between times?”

“I’m kind of thinking more about a slow process of developing something for the day when we will be able to come together again,” she says, and pauses.

“But I don’t know, maybe that’s a bit short sighted or something.”

Power’s artwork has mostly been in sculpture and video art, this was to be her first live performance. But its creation has been forced to happen through a screen.

“It makes me think: maybe the live element isn’t necessary?” Power says, only half-asking. “But I just feel so committed to keeping on trying.”

It feels we are experiencing a glut of online performances: pre-recorded shows on YouTube; companies staging play readings via Zoom; cabaret via Instagram. And yet, I have been feeling like these grasps at relevance have been empty. I don’t have the space – emotional or mental or physical – to connect to this work. It just reminds me what we have lost.

“I’m so interested in connections and intimacy and how we interact,” Power says. “The same kind of format but filmed and then put online, or a live event but online, I just can’t engage with that.”

If the last three months have taught us anything, it seems planning ahead for a future is a furphy. How can you imagine a future when the truth of your present shifts every day? What does it mean to think about performance and coming together, when we have no idea how long COVID-19 will disrupt our lives? Thinking about the future is always part of making an artwork: thinking of its future state, its future form, its future audience. Alone in Waterside Workers Hall, perhaps for Power these thoughts of an unknown future are perhaps louder than they would usually be.

“Every time I walk into the main hall,” says Power, “I think about the future and when I’m back in that space and how weird it will be to reflect on this time when it’s bustling again. Imagining when I’m at the next Adhocracy and being like: remember when you spent heaps of time alone in here?”

“It’s such a social place. and all of my associations are to do with connections and conversations and exchanging of ideas, so to walk in with the presence of that but not tangibly … “ she trails off.

“I think it means it feels really beautiful to work in because you are surrounded by that [energy] constantly, through memory and architecture.”

I tell Power how I have been thinking less about live performance, and more about the conversations in the foyer afterwards. The sharing of art in space and in time, conversations happening incidentally but crucially. “Those conversations can be so minimal, or seemingly unrelated, even, to what you’ve seen. Whatever picks up from that moment when it ends,” she says..

The liveness, “kind of cracks [an artwork] open more.”

“If you think about seeing a video in a gallery or a sculpture in a gallery there is that intimacy that is quite narrow, in a way.” But, she says, of performance, “there is an energy of continuing it on.”

Adelaide feels so removed from the world right now. We have been so lucky in how few cases we have had, how short a time we were in lockdown before things started to open up again – how lax our lockdown rules were, in any case.

But is there anything Power feels like she could carry forward from this period of time?

“Boundaries, I think,” she says. “I’ve been finding it easier to maintain boundaries for when things are right. I guess because I’ve been not socialising as much, I’ve realised how little I need to socialise.”

“You just don’t have to.”