Vitalstatistix spoke with Hilary Kleinig from Zephyr Quartet and Jennifer Greer Holmes, independent creative producer and ZQ’s manager, about contemporary and experimental music, their focus on collaboration and how they are feeling about the future of Australian arts three weeks after what’s become known as Black Friday.

V: Zephyr Quartet is really forging a reputation for experimentation and interesting collaborations. Tell us about some of your recent projects.

HK: Our most recent major project in the Adelaide Festival, Exquisite Corpse, is a musical version based on the Surrealist parlour game of the same name. Instead of passing fragments of text or drawings from one person to the next, we commissioned twelve composers from Australia and the USA to write a 65min seamless score, whereby one composer would pass the last fragment of their section onto the next composer as a starting point for the following section. For this project we also worked with visual artists Jo Kerlogue and Lukukuku who created an animated visual response to the music that was projected into the performance space.

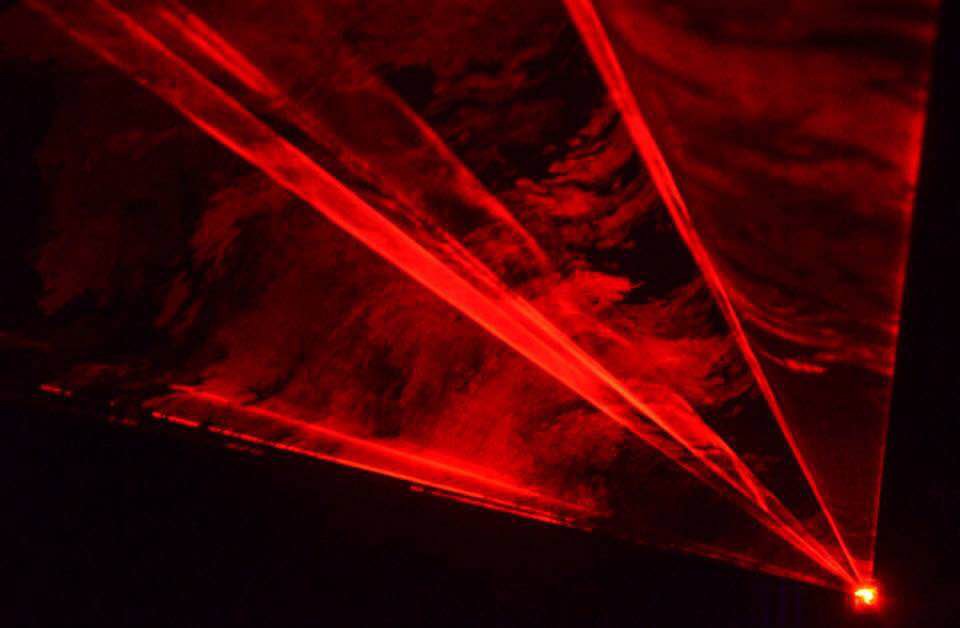

Another of our favourite recent projects is Between Light, which draws together five jazz musicians to compose a new piece for Zephyr in response to the theme of ‘chiaroscuro’ – the Italian art term used to describe the effect of contrasting areas of light and dark in a painting or drawing. We then invited Geoff Cobham and his team of Chris Petridis, Lachlan Turner and Alexander Ramsay to respond, not only to the music but also to the space in which we were performing the pieces (for the premiere season this was at Queens Theatre). They created a ‘house’ for each piece by using different parts of the building and utilising separate installations that responded uniquely - using varying notions of light and dark – to each piece of music and the space. During the performance, the audience moved around the space with the quartet as we performed and joined us in an intimate conversation of music, light and space. We liked this project so much that we wanted to do it again and are really thrilled to be able to explore Between Light in a new space at Vitals’ wonderful Waterside Workers Hall.

JGH: Zephyr’s approach to collaboration is what drew me to working with them. It’s at the heart of everything we do: artistically; the way we make decisions; everything is a discussion, everyone plays a part. I’m constantly bewildered by how successful the collaborative process is with ZQ – sometimes we are talking about projects with more than twenty artists involved, often from multiple cities or countries. It’s an interesting and satisfying process of working.

V: There seems to be flux and development in contemporary and experimental music in South Australia at the moment – why do you think that is?

HK: I am very proud to be a part of a dynamic and talented music community here in South Australia, and I think the quality of music making here is extraordinary and world-class. Whilst there are things that I personally would like to see more of in the music scene, what I see as a big part of the success in the form of flux and development is the sense of community from a large part of the sector – a willingness to support each other in playing for projects, by going to each other’s performances, recording each other’s music and getting excited about what other people are doing. I think that COMA (Creative Original Music Adelaide), who run a performance series at the Wheatsheaf Hotel, have had a large impact on bringing together musicians from different genres and supporting a creative community, too.

V: ZQ’s recent projects have seen the Quartet collaborate with other established South Australian artists across artforms. What is the collaborative experience like for the Quartet?

HK: Collaboration is key to what we do, and the nature of the collaboration changes from project to project. We are very interested in adopting theatre and dance models in terms of creative development for producing work (although on a smaller scale), however this is rarely supported by funding bodies because it is a practice not utilised in music, especially not on a collaborative level.

I feel that there is a great depth and authenticity within work generated from a ‘ground-up’, collaborative practice and we Zephyrs are interested in making work that speaks deeply, uniquely and personally to a people, a time, and a place.

Sometimes this means finding existing music and placing it within a certain context or environment, but often it means creating from scratch – which of course is more risky and hard to promote because you don’t know exactly what it will be like until you perform it! For instance, when we premiered Between Light, I remember such a profound sense of relief after the first performance that it ‘worked’ – I really couldn’t tell if it would from an audience perspective! (I then proceeded to tell all my friends to come along!)

It is great for us to be able to have opportunities to present projects again. Aside from the vast amount of energy, time and money it takes to create projects such as Between Light and Exquisite Corpse, a remounted presentation (again, not such a common occurrence in the music sector) offers us a certain peace of mind, in that we have an idea of what the outcome will be for us and our audience, as well as the chance to make something good even better!

V: What are you thoughts on the opportunities available to mature independent contemporary artists in South Australia – what are the benefits and disadvantages of working here?

JGH: On the one hand, the opportunities that Adelaide offers are largely due to the ease of making relationships with people. It means that, personally, I have found work easy to come by because after all this time I have a really diverse network of peers in multiple art forms, and outside of the arts. It’s the main thing that’s kept me in Adelaide – I haven’t wanted the challenge of rebuilding that. Also, it’s a relatively cheap lifestyle: a person can live fairly easily on a fluctuating income. This means that there are loads of artists doing interesting things.

Of course, there’s also access to funding, and some initiatives for development, in-kind support and residencies.

Having said all that, and with the bright eyes of someone who is currently travelling in Berlin, the disadvantages are more apparent. Over the past few years, the isolation of being in Adelaide has got under my skin. Shows that I want to see don’t tour here (whether that’s an experimental intimate theatre work, or someone as mainstream as Madonna) – so to remain engaged in national and international performance we have to travel. I love travel, but it’s disruptive, expensive and not always possible. I’m interested in what’s happening right now – although I have concern for the future and respect for the past – and I feel I am neglecting my professional responsibilities if I don’t see contemporary performances. So, it’s either travel, or waiting and hoping that presenters like Vitals or one of the major festivals tour contemporary works into Adelaide.

The other disadvantages are that I often feel the sector in Adelaide is stifled by a lack of politicisation, a lack of forward thinking (but present-acting) leadership, too many gatekeepers, and a vast misunderstanding by some decision makers about what it actually takes to be an innovative maker of live art. And then, perhaps it’s the flip side of what I was saying before… It’s a small town. Everyone knows everyone, so it can be hard to find freshness – both personally and professionally.

V: Tell us about Between Light and why ZQ wanted to present the work with Vitalstatistix at Waterside.

JGH: I have a really strong connection to Waterside and Vitals, stemming from my family’s history with the building, growing up in the area, and my work with Vitals – as a former staff member, a documenter of events, and as an independent artist. Vitals is the state’s only presenter supporting innovative, experimental, cross-disciplinary collaboration in a way that is affordable for independent artists and small organisations. When Emma Webb responded to the premiere of Between Light at Queen’s Theatre so positively, I immediately thought that it would be a good work to see in that spectacular old hall, Waterside.

HK: Between Light was always conceived as an adaptable touring show and, in essence, a conversation between three elements – music, light and space. What is special about the music created for Between Light is each score comprised an improvisation component, which means we will never perform – and audiences will never hear – any piece quite the same way twice. Likewise, the lighting is stimulated, manipulated and generated live manually and through technology that turns sound waves to light. To be able to explore the possibilities of a different space adds yet another dimension to the life of this project, and we are very excited about this!

I also deeply admire Vitalstatistix’s role in our artistic community – Vitals are game changers, leaders and fearless producers of work that has national and international impact. I personally admire the way the organisation delves deeply into the local community, history and a broader social commentary to support artists and create work – I feel humbled and proud to be able to be a small part of this.

V: Jennifer, you work across a range of art forms as a creative producer, arts manager, curator, documenter, DJ and other roles. How do you approach your relationship with artists and your career as an independent cultural worker?

JGH: In short, from the heart. I have been evolving my ‘rules’ for how and who I work with over the past five or so years. When I first decided to give this whole independent caper a crack, my only motive was to not work with dickheads or Boards. Now, I have refined that somewhat!

When I work as a creative producer, I mostly work with friends (or artists who have been recommended by friends) who are trusted, both personally and as artists. I’m not interested in working with people or on projects that I wouldn’t want to see or artists I can’t advocate for the type of work they do. That’s not to say I haven’t done that – I’m just not very good at it.

In terms of artist management, again, I only do that for friends. At the moment, I work with Zephyr, Jason Sweeney and Heath Britton. I want to work with people I can be brutally honest with, for better or for worse (and it’s no coincidence that I use that marriage vow – I see it as a bond and an honour like no other).

I’ve been with Zephyr for more than four years, which is the longest job I have ever had. I love it and I love them. I think they’re completely shit-hot and I have had the privilege of talking about them overseas for the last month and a half – and people are so impressed.

They’re really leading the way. I already knew that, but having spent this time away and seeing what else is out there, it became even more obvious.

As a documenter, I see myself as a tiny cog in the process of telling a story. That’s a weird one to me, the documentation. It kind of just happened, without any deliberate choice. I think it’s vitally important to have records of things, and I’ve always been obsessive about hoarding memories, so it totally fits with my history and personality that I would do this for work. It is quite technical (which isn’t me at all) – I work with Heath Britton in this role, who I have known for over 20 years, so we have a shared language and defined roles that we’ve slipped into with making videos for artists.

Being a DJ is my favourite job I’ve done. It’s purely indulgent, hedonistic, joyful and outrageous. I work with a dear friend, Jo Kerlogue, and we get paid to drink bubbles, play our favourite records, dance and watch other people dance. If I could do that every day for the rest of my life I would be a very happy lady. Also, being a ‘post-modern feminist vinyl only DJ duo’ means that we kind of have a particular niche! It’s still work, and sometimes it feels like “going to work” but there is no comparison to a bad day at the Bad Jelly office – it’s still pretty darn good. In terms of collaboration, and the way Jo and I work together, pretty much we are just old mates who love records and tell each other how it is.

Back to the short answer though: I don’t do work that I don’t believe in. I can’t. When I stop enjoying something I don’t feel like I am being true to myself if I keep doing it. Work is very personal to me. Sometimes that’s problematic; most of the time it’s fucking fantastic.

V: You have worked with Vitalstatistix in many different capacities over the years. What do you see as the current value and role of Vitalstatistix?

JGH: As I mentioned before, Vitals is pretty much a standalone in Adelaide and South Australia in terms of the opportunities it offers artists. I have been fortunate enough to benefit from being an Incubator artist, which supports the development of new work; I’ve documented every Adhocracy since it started and am just astounded at the way that it continues to evolve the way it supports and engages artists and audiences. It’s completely unique in Adelaide, there is simply nothing like it. I love it. It’s my favourite part of Vitals’ programme.

Vitals is there for independent artists. It has helped develop audiences’ understanding of and taste for live contemporary art. It has facilitated so many creative relationships and sparked multiple collaborations that I have directly benefited from – both as an artist and an audience member.

In relation to the current funding situation, I always felt Vitals should be safe due to the unique offering they make to local and national artists. No-one else is doing what Vitals does, and no-one else has the kind of impact Vitals does in terms of public outcomes on the kind of money that’s available. Post-funding announcements, I am completely devastated by the news that Vitals missed out on funding. I have no words… Ok, maybe some: Shocked. Gutted. Appalled.

V: How are you feeling about the future of the arts locally and nationally?

JGH: Every time I think about this question I try not to be bleak. Yet, here I am again, attempting to answer it and feeling bleak. Not in terms of the art that is being made (there are truly exceptional artists here) , but the opportunity for artists to make it with adequate support for their work – not just funding, but infrastructure: both physical, such as venues; and in education, such as audience development and training.

That aside (and I don’t cast it aside lightly, I’d just prefer to focus on something that gives me hope), the emergence of a strong and diverse live art scene in Adelaide over the last few years is largely what’s kept me there. And it’s no coincidence that I am writing this for Vitals, as it is Vitals who has been at the forefront for supporting this type of work locally.

When I think about making work in Adelaide and Australia at the moment, I feel a bit limited. We are insular, we must reach out to be part of conversations, for it is rare that we are invited into them. For the most part, I don’t feel this is especially problematic: it definitely informs the experimental nature of our work, as I feel we are somewhat uninfluenced by trends. However, it does have limitations for audience growth – not just in numbers (which is an obvious one) but for the growth of an audiences’ understanding of what else is out there, what they can demand from their engagement with artists and the type of work they can see.

I’ve been writing this blog from various parts of the world – all away from home (I’ve been to 15 cities in just under 7 weeks!). I’ve been incredibly fortunate through my work in this sector to be supported to attend markets and festivals in order to find presentation and collaboration opportunities for SA artists. I am in love with Europe, and absolutely see the increased potential for artists to work there. I imagine it’s for a range of reasons, but one of the things I noticed in my conversations with Europeans from a variety of backgrounds (cultural, social, economic, language) – is the acceptance of the arts. It made me sad for Australian artists: I feel that we are apologetic or defensive of our choice to do creative work.

Again, short answer: it feels bad and sad. The devastation of the Australia Council news is fresh and I am tired of being told we need to find new ways to survive – as if we aren’t already doing that! Three companies I’ve worked with a fair bit in the past two years haven’t been funded. And I guess the other thing that has me down – particularly now, as I arrive back in Oz – is the potential of Adelaide to be this great city for arts and artists. There are amazing cities all over the place which have half - or less than half – the population of Adelaide which are all absolutely thriving with stuff to do and people who are out there hungry for it, publications who pay writers to write about it, and businesses who rely on the arts to bring people through their doors. It has nothing to do with our size. It’s an excuse we’ve been hearing for ages. I don’t know how to address it, I feel like I’ve been trying for half my life and am a tad battle weary. When the fight outweighs the joy – that’s a sign for me.

HK: There are no doubts that these are fairly dark times for the arts and I see the more recent Australia Council funding cuts as just yet another nail in the coffin. A myriad of things have contributed to making a hard job even harder over the last 5-10 years – ABC funding cuts, changes and cuts to arts courses at university and TAFE, etc.

I too, at times feel incredibly sad about this and echo Jennifer’s laments about the place and importance of culture within Australia, and I am not sure what to do to make changes to this. What we are talking about here are fundamental changes to our national identity! In a real practical sense I do feel that vast changes at a fundamental levels need to be addressed in education, access to arts, and media.

On a positive note over the last month or so I have felt a sense of purpose, of coming together, of unity and strength from the vast majority of the arts sector on many different levels. People are realising that they do have a voice, that they can speak for change, and that this is better done from a united front. Whilst none of us know what the future will hold there is a sense, for the most part, that we are all in this together, and that we are a community that – despite our differences – want similar results and outcomes.

I can’t speak for others, but these are my feelings today, right now, in this time and place:

I, too, feel that sometimes the fight is too much, that I am tired and have nothing left to give. On the other hand, at times, and most recently this last week, I am reminded by the power of art, the power of community and the power that a sense of shared experience in time and place is a strong and important reminder of our common, shared humanity.

On Monday I had the honour of playing music for a friend’s funeral – it was sad and it was happy, it was funny and it was joyful. Trying to read the music and play the right notes through the tears, trying to make a beautiful, moving sound that would honour a life well-lived, and looking at the vast crowd of people who were there sharing in this most primal human experience, I was reminded that music says things that words can’t say, that art has a power that no one can undermine and that it is our shared humanity and a strong sense of being part of and being valued by a community which makes life worth living.

I don’t know that will happen in the future with governments, with funding, with arts bodies, with politics, and what this means for the future of the arts locally and nationally. I know that changes in these areas can make our jobs as artists easier or harder but it can’t and won’t ever take away the power of and our human need for art.

Zephyr Quartet presents Between Light in association with Vitalstatistix, 30 June – 3 July.